Vocation/Vocación : A special summer

sa

Piscando la cherry

Hace dos día, escribí de hacer ministerio con trabajadores migrantes del campo. Una de las mejores aventuras de mi vida fue cuando pasé un verano piscando cerezas como parte de un año sabático.

Picking cherries

Two days ago, I wrote about doing ministry with migrant farm workers. One of the best adventures of my life was when I spent a summer picking cherries as part of a sabbatical.

En el campo con los trabajadores migrantes

Había aprendido mucho sobre las vidas de los migrantes en los diez años que ofrecí programas de catequesis para trabajadores del campo en los campos migrantes en Oregón y California. Vi el trabajo y las condiciones de vida y conviví con muchos trabajadores del campo, pero nunca había trabajado en el campo ni en la cosecha. Durante mi año sabático en 2007, pasé tres meses siguiendo a los trabajadores desde Stockton, California a Oregón y a Washington. Parte de este tiempo, viví y trabajé con migrantes pizcando cerezas en Stockton. En otras partes, me quedé en las rectorías. Visité los lugares de trabajo, campos y ministerios ofrecidos por las iglesias locales de California, Oregón y Washington.

Me puse de acuerdo con un contratista en Stockton para vivir con los trabajadores en el campamento pizcando cerezas con una familia distinta cada día. Mientras trabajaba, podía platicar con ellos y aprender sobre sus vidas como trabajadores migrantes. Viví en el campamento migrante. Trabajé para entender las vidas de los trabajadores, compartiendo lo que tenía con ellos como tantos de ellos compartieron conmigo. Compré lo que necesitaba en el pueblo con los otros trabajadores, pateé una pelota de fútbol, jugué baloncesto y aprendí juegos de baraja que nunca había conocido. Aprendí la rutina de vivir en un campamento migrante.

En mi primer día en la huerta, mientras pizcaba cerezas, los que no me conocían preguntaron: “¿Quién es el gabacho trabando con nosotros?” Muchos no podían creer que yo era sacerdote. Al principio, había algunos que no se sentían a gusto con mi presencia. Algunos terminaban el día con una cerveza y la escondían cuando me veían. Al día siguiente, la mayoría se sentía más a gusto y me preguntaban cuantas cajas había pizcado. Varios me ofrecieron una cerveza.

Hay aspectos de la vida migrante que yo no podía compartir. Yo no estaba trabajando para sobrevivir. No tenía una familia que dependiera de mi. Como americano, tenía seguridad. Yo sabía que podía irme a cualquier hora, y como el acuerdo con el contratista era que no recibiría un sueldo, no tenía presión de cuanto lograba en mi trabajo. El pago de las cajas de fruta que yo pizcaba se le agregaba a la gente con la que yo trabajaba. A la tercera noche, declaré que al siguiente día yo “calificaría”. Uno necesitaba pizcar doce cajas de cerezas para ganarse el sueldo mínimo, y yo estaba intentando lograr eso. Los trabajadores no querían que yo usara una escalera. Se preocupaban de que me fuera a caer. Yo insistí en aprender a trabajar en una huerta. Al cuarto día, aprendí a usar la escalera y empecé a pizcar las cerezas con más agilidad. Al final del día, Joaquín me gritó: “Padre, ¿cuántas cajas pizcó hoy?” Le respondí: “Catorce”. Todos aplaudieron. Luego le pregunté a Joaquín: “¿Cuántas cajas pizcaste tú?” Él respondió: “Cuarenta y dos”.

Hay bendiciones sorprendentes cuando uno se concentra solo en pizcar fruta bajo un árbol. Las preocupaciones del mundo desaparecen mientras uno se adentra en el ritmo de pizcar la fruta. Los ruidos en la huerta incluyen los pajaritos y los radios distantes tocando música latina. Se escucha el ruido de éxito mientras las cerezas caen en el balde. Plunk, plunk, plunk. Es buena noticia cuando uno escucha los gritos avisando que la “lonchera” ha llegado. El trabajo se detiene por un tiempo mientras los trabajadores compran y consumen comida de la “lonchera”. Los trabajadores platican de sus familias y de sus pueblos natales.

La cosecha de la cereza termina entre las dos y las tres de la tarde. El calor del sol cae sobre la huerta y la gente regresa a sus viviendas. Algunos se quedan en el pueblo con amistades o parientes en casas, algunos se quedan en viviendas que provee el dueño de la huerta, pero muchos se quedan en campamentos bajo los árboles en la huerta.

Después de haber vivido dos semanas en Stockton, California, fui a The Dalles, Oregón para el programa de catequesis que me introdujo a los trabajadores migrantes. Algunos con los que viví en Stockton también se fueron a The Dalles. Otros se fueron en otras direcciones siguiendo distintas cosechas. La experiencia de pizcar cerezas me abrió muchas puertas con los trabajadores migrantes. Algunos no podían creer que yo realmente había pizcado cerezas. Un hombre en The Dalles no lo podía creer hasta que le dije el nombre del contratista y describí la huerta donde me quedé. Se convenció cuando le describí la huerta, especialmente cuando le conté que otros trabajadores y yo teníamos que bañarnos en un arroyo porque solo había dos baños para casi 100 trabajadores.

(Mañana: Director del Ministerio Campesino)

In the field with migrants

In ten years offering catechetical programs for farm workers in migrant camps in Oregon, I learned much about the lives of migrants. I saw the work and the living conditions, and I visited with many farm workers, yet I had never worked on a farm or in a harvest. During my sabbatical in 2007, I spent three months following workers from Stockton, California to Oregon and Washington. Part of that time, I lived and worked with migrants picking cherries in Stockton. In other places I stayed in rectories. I visited work sites, camps and ministries offered by the local churches in California, Oregon and Washington.

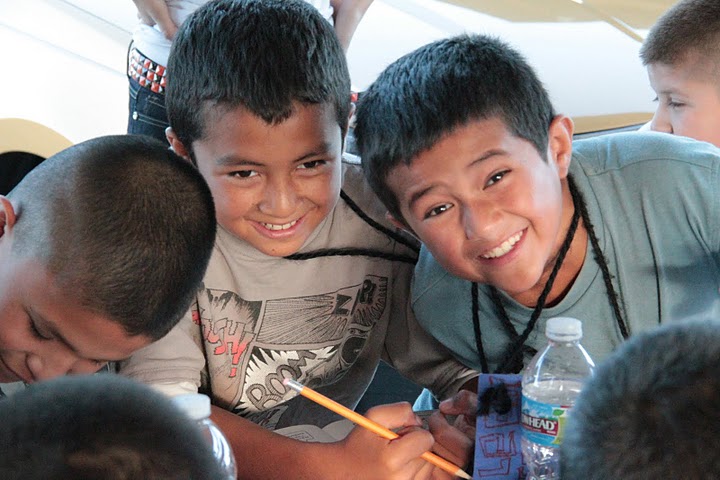

I made arrangements with a contractor in Stockton to live with workers in a camp, picking cherries with a different family each day. As I worked, I could chat and learn about their lives as migrant farm workers. I lived in the migrant camp. I worked to get in tune with the lives of the workers, sharing what I had with others as so many shared with me. I bought necessities in town with other workers, kicked around a soccer ball, played some basketball and learned card games that I had never known. I got into the routine of a migrant camp.

My first day in the orchard, as I picked cherries, those in the orchard who did not know me asked, “¿Quién es el gabacho trabajando con nosotros?” (Who is the American working with us?) Many found it hard to believe that I was a priest. At first, there were some who were not comfortable with my presence. Some would end the day with a beer and try to hide it when they saw me. The second day most were more comfortable and would ask how many boxes I had picked. Several offered me a beer.

There are aspects of migrant life I could not share. I was not working for my survival. I did not have a family depending on me. I was secure as an American. I knew that I could leave at any time, and as my arrangement with the contractor was that I would not be paid, I had no pressure on how much I accomplished in my work. The boxes of fruit that I picked were credited to people with whom I worked. The third night, I declared that the next day I would “qualify”. One needed to pick twelve boxes of cherries to make minimum wage, and I had been working up to that. The workers did not want me using a ladder. They worried that I might fall. I insisted on learning how to work in an orchard. The fourth day, I learned how to use the ladder and began to get a better rhythm in picking the cherries. At the end of the day, Joaquin cried out to me, “Padre. How many boxes did you pick today?” I responded, “Fourteen.” All applauded. Then I asked Joaquin, “How many did you pick?” He responded, “Forty-two.”

There were some surprising blessings working under a tree focused only on picking fruit. The worries of the world outside go away as one gets into a rhythm picking the fruit. The sounds of the orchard include the birds and distant radios with Latin music. There is a sound of accomplishment as the cherries fall into the bucket. Plunk, plunk, plunk! It is good news when one hears the cries that the lonchera (lunch truck) has arrived. Work stops for a time while food from the lonchera is purchased and consumed. The workers visit and talk about their families and hometowns.

The cherry harvest ends around 2:00-3:00 p.m. The heat of the sun comes over the orchard and people return to their housing. Some return to town to stay with friends or relatives in homes, some in housing provided by orchardists, but many stay in tents under trees in an orchard.

After living two weeks in Stockton, I went to The Dalles, Oregon for the catechetical program that introduced me to migrant farm workers. Some of those with whom I lived in Stockton also went to The Dalles. Some went in other directions to follow different harvests. The experience of picking cherries opened many doors for me with migrant workers. Some found it hard to believe that I actually picked cherries. One man in The Dalles would not believe it until I told him the name of the contractor and described the orchard where I stayed. He was convinced when I described the orchard, especially when I said that the workers and I had to bathe in the creek as there were only two showers for nearly 100 workers.

My summer picking cherries is one of my fondest memories as a priest.

(Tomorrow: Director of Campesino Ministry)