Migrant Faith, Chapter Five: Who is the Campesino? (Cont.)

Who Is the Campesino?

- “Skilled Agricultural Workers”

Counter to myths in the news/entertainment industry and in political circles about the migrant as an “unskilled worker”, agriculture needs a work force that has a significant variety of skills. It takes training to properly produce and harvest crops for the marketplace. The work done by these workers is a trade and it is wrong to identify trade skills as unskilled labor. In an interview with Mr. Bob Bailey, CEO of Orchard View Farms in The Dalles, Oregon, Mr. Bailey consistently called his workers, “my skilled agricultural workers.” Migrant farm work needs to be viewed as a trade, a learned skill.

Harvest work demands a variety of skills. Beginning workers may be untrained, but soon they must learn how to pick the fruit without bruising it, and how to pick the fruit properly so as not to damage the tree which affects the future production of the tree. They learn the art of placing a ladder. An untrained cherry worker may pick twenty buckets of cherries in a day, while a skilled worker picks fifty or more a day.

When an owner hires a worker, a skilled worker is important since the skilled worker picks fruit with minimal impact on the tree and will pick what two or more untrained workers may produce. With patience, an owner recognizes that an untrained worker needs experience to learn the trade, but the owner needs a healthy percentage of skilled workers to have a profitable orchard. With workers who are less skilled, one needs more workers and there are the additional costs of housing, ladders, supervision, accounting, bookkeeping and other expenses.

- Mobility.

Migrant workers are mobile. They follow the crops when they are ready. When the harvest comes, they move in to pick the crop until finished and then move to the next harvest. A good harvest for the worker is measured by the number of days worked and the number of buckets they pick. A good harvest for the owner is measured by the quantity and quality of the product.

For many, the image of a migrant worker can be seen in Luis H. Each year Luis comes to the U.S. in March to begin his work in California. He spends several weeks trimming trees and vines. He moves with each crop to different sites on the West Coast. In May and early June, he picks cherries in Stockton, and then goes to The Dalles, Oregon for more cherries. From there, he follows the cherry, pear and apple harvests in California, Oregon and Washington. In November, he returns to Mexico to be with his wife and children. He hopes to make between $15,000-25,000 during his time in the U.S. He says that he averages making about $100 per day. Some harvests pay more than others. He hopes to work 200 or more days in eight months. In 2006, he worked 210 days. He is not here for tourism or vacation, but to make a living to support his family and allow him to build a home in Michoacán. For many people, Luis is the image of a migrant worker.

While the cherry harvest in The Dalles has a traditional appearance, there are few workers like Luis among the migrants with whom I have worked. More are like Alberto who lives in a town near Fresno. Alberto does the exact same work as Luis, but with the exception of picking cherries in The Dalles, his work is found within sixty miles of where he lives. He spends several weeks harvesting a variety of fruits during their seasons and spends the winter pruning trees and vines. His life appears stable as his children attend school in the town and he returns to his house each evening.

Still, Alberto is a migrant worker whose stability or instability in life is directly affected by the mobility of his work. Many workers in the situation of Alberto are as uncertain as Luis of where they may be in the next month. The nature of migrant life is to be mobile; the work is temporary, and the worker has multiple skills. The instability of the worker is complicated when the worker or one of his family members lacks legal documents. Local action taken by Homeland Security, rumors and fear keep families in a constant state of insecurity. This insecurity keeps many from establishing ties with local churches, schools and community organizations.

- The faith of migrants

Agricultural migrant workers are ordinarily Catholic. They tend to come from rural Mexico and Latin America. Their faith is deeply rooted in family expressions of faith. Devotional prayer, celebration of feasts and devotion to the Virgin nurtures the faith. Few have received significant catechetical instruction. Still, the migrant worker is profoundly Catholic and lives that faith in a simplicity that can inspire those with higher levels of education.

In 2007, I visited a gentleman in Michoacán. He worked nearly forty years picking fruit in California, Oregon and Washington. Each year, he returned to his beloved town of Galeana. At age 62, he stopped coming north for the harvests. When I entered his home, he kissed my hand and said, “Padre, it is a blessing that you enter my house.” He then fumbled under his shirt and pulled out a cross that I give to workers at the end of our migrant camp Masses. It is a simple plastic cross that reminds people of the blessing given to the workers of the cherry harvest. He said, “I have two more in my room. It was such a blessing to have Mass in our orchard.”

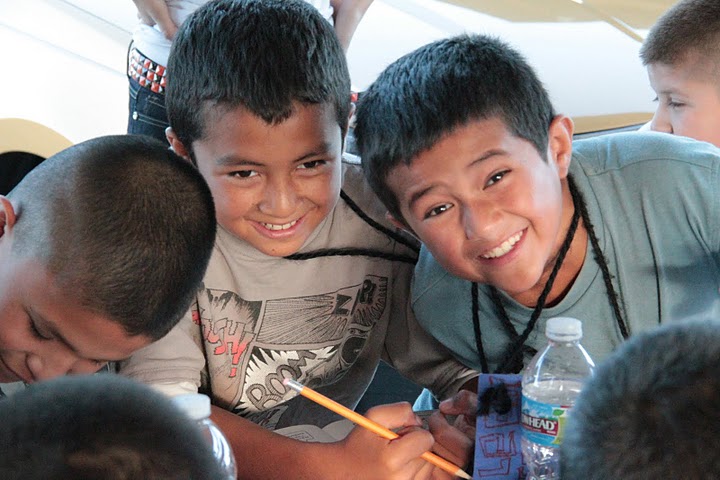

The Masses that I offered in the orchards of The Dalles, Oregon are a small act of grace received by the workers, but their gratitude over the years has always humbled me. After thirteen summers of offering Masses in camps during the cherry harvest and eleven years of running a catechetical program for children of migrants preparing for First Communion and Confirmation, the depth of Catholic faith found among people who are at the margins of our church amazes me.

There is a discouraging aspect of the faith of migrants in how deeply they are aware of unworthiness. There is a profound sense that they are not good Catholics. They have been lectured continually on their unworthiness because of their lack of regular attendance at church, their lack of catechesis and the irregularities of marriages. Many internally believe that they are “bad people.” It is difficult to guide them to trust in God’s mercy and love. For example, twelve men that live on a sod farm have no vehicles and live several miles from the closest town. They work under a contractor for ten hours a day, seven days a week. They are paid minimum wage, no overtime. They live in housing provided by the farmer, and they pay $12.50 per day for food that is provided at the camp. With no transportation and a work schedule that never gives them a day off, they obviously cannot attend Church regularly. Yet if they are asked to be a godparent for a baptism, local churches give them a hard time or refuse to let them be a “padrino.” People in ministry need to walk with migrants and understand the life that they live.

- Working Conditions and Wages

The living conditions, treatment and pay of migrant labor vary from one location to another. The disparity of working conditions again makes generalizations difficult. The living conditions that I experienced in Stockton, California were dramatically different from what I experienced in The Dalles, Oregon. In The Dalles, the owners are present in their orchards and are “hands on” in the work of the harvest. They mingle with and know many if not all of their workers. In Stockton, I did not see a similar contact of the owners with the workers since many orchardists employ contractors. It is the contractor who has direct contact with the workers.

Wages are not the only consideration of the migrant worker in seeking work in a particular orchard or farm. The worker considers what it will cost to live in the area during a harvest to determine the value of going to one harvest or another. In some communities, the orchardist or farmer provides housing. In other areas, people need to rent lodging or sleep in tents at the back of an orchard. One worker said of his work picking cherries in both Stockton and The Dalles, “I make more money in Stockton, but I take home more from The Dalles because of the housing offered by the orchard owner.”

The problem of low wages is the reality of agricultural economy. The wages of the migrant worker are modest, but when workers are able to minimize their expenses with housing and with consistent work, they can make a reasonable living. Harvest workers look for a good number of full days of work. When the migrant comes to a community, he is looking for steady work that makes the sacrifice of being away from home worthwhile. He is not looking for days off.

Workers are paid the minimum wage mandated by state law for agricultural workers by the hours worked. In many harvests, there are incentives for higher production. With incentives in those harvests, workers may make between $10-20 per hour. Unfortunately, not all agricultural work has incentive levels that raise the pay sufficiently. The threshold for reaching incentive levels in the cherry harvest in a normal harvest situation is fairly easily attained and workers may double or even triple minimum wages in the cherry harvest. I visited a nursery in northern California that had incentive levels that very few workers could attain. So basically, workers could make no more than minimum wage. In some agricultural work, workers are paid simply by the hour. Minimum wage rates for migrant workers simply do not provide for the needs of a family.

Sometimes there is a quota of how much fruit or product may go to a packing house in a day. If the quality of the fruit coming to the packing house is low because of rain damage or such, the packing house may place limits on how much fruit may be processed. If the workers reach the limit early, the workers may only get in three to five hours of work. This lowers their income for the harvest season. Obviously, weather, quality, and quantity of the fruit affect the harvest.

Unfortunately, there are times when an orchardist or a contractor may have too many workers so that the work day ends early as a block of trees or a field is finished in less than eight hours. Workers understand when an orchard has limited work because of the nature of agricultural work. However, there are hard feelings when the work is limited because of having too many workers.

In those agricultural jobs that pay only by the hour, there are some serious problems. Many workers are pushed to work extremely long hours, from ten to twelve hours per day and they are working six and seven days a week. They are not paid overtime while working sixty or seventy hours a week. Long hours are especially common in dairies and feedlots.

Contractors provide workers for a specific work or harvest. They are a layer of administration between the owner and the worker. This may provide a convenience and protection of the owners from U.S. government regulations on immigration and workers protections, yet some contractors take a bite out of the income of the workers. Contractors can manipulate their workers to work more hours by using the desire of the worker for more income and by intimidation either by threats about immigration or by threats that someone else will take the job.

- Avoid stereotyping

There is neither a stereotypical farm worker nor a stereotypical contractor or farm owner. I present observations about workers, employers, and contractors with a conscious awareness that all are about the business of agriculture. The conditions of workers vary in many situations. In some cases, there are injustices, but my overwhelming experience with people in all aspects of agriculture is that they are good people, putting food on the tables of the world. Those who administer their workers and farms poorly cause grief for the many conscientious people in agriculture. Difficulties in the lives of farm workers come from many sources.

No easy answers

The complexity of the lives of migrants and the realities of migration call for a comprehensive approach on the political issues around migration. The same is true in matters of faith. We need a comprehensive approach to evangelization and the outreach of the Church to the migrant. Simplistic answers to complex problems will leave society and the Church divided and unhappy with unworkable solutions.

Migrants are hardworking, hopeful and faithful. With a little attention on my part, they have taken me in as their priest. Their love is genuine and humbling. My hope is that others may love them and care for them both in our society and within our Church.

¿Quién es el Campesino?

- Trabajadores agrícolas especializados

Al contrario de los mitos en la industria de noticias y entretenimiento y en círculos políticos que dicen que el trabajador migrante es un “trabajador sin especialidad”, la agricultura necesita una mano de obra que cuente con una variedad de destrezas. Se requiere preparación para sembrar y cosechar cultivos apropiadamente. El trabajo que desempeñan estos trabajadores es un oficio y es incorrecto identificar un oficio que requiere destrezas como “mano de obra no especializada”. En una entrevista con el Señor Bob Bailey, jefe ejecutivo principal (CEO) de Orchard View Farms en The Dalles, Oregón, el Señor Bailey consistentemente se refería a sus trabajadores como: “mis trabajadores agrícolas especializados”. El trabajo del campo debe considerarse como un arte, un arte que se aprende.

El trabajo de la cosecha exige una variedad de destrezas. Los nuevos trabajadores pueden tener pocas destrezas, pero pronto tienen que aprender como pizcar la fruta sin dañarla y como pizcar la fruta apropiadamente para no dañar al árbol pues esto afecta la producción del árbol en el futuro. Aprenden el arte de acomodar una escalera. Un pizcador de cereza sin preparación puede pizcar veinte baldes de cereza en un día, pero un trabajador preparado pizca cincuenta baldes o más al día.

Cuando un ranchero emplea a una persona, un trabajador especializado es más importante porque pizca la fruta con mínimo impacto al árbol y pizca lo que dos o tres trabajadores sin preparación pueden pizcar. Con paciencia, un ranchero reconoce que un trabajador sin entrenamiento necesita experiencia para aprender el oficio, pero el ranchero necesita un buen porcentaje de empleados especializados para obtener buenas ganancias. Con trabajadores que tienen menos habilidades, se requiere más personal resultando en costos adicionales de vivienda, escaleras, supervisión, contabilidad, teneduría y otros costos.

- Movilidad

Los trabajadores migrantes son móviles. Siguen la cosecha cuando los cultivos están listos. Cuando empieza la cosecha, pizcan hasta que terminan y luego siguen a la siguiente cosecha. Una buena cosecha para los trabajadores consiste en el número de días que trabajan y la cantidad de baldes que llenan. Sin embargo, para el ranchero, una buena cosecha consiste en la cantidad y la calidad del producto.

Para muchos, Luis H. es la imagen de un trabajador migrante. Cada año, Luis viene a los Estados Unidos en marzo para empezar su trabajo en California. Él pasa varias semanas podando árboles y viñas. Se muda con cada cultivo a distintos sitios de la costa oeste. En mayo y a principios de junio, pizca cerezas en Stockton, California, y luego se va a The Dalles, Oregón para pizcar más cerezas. De ahí, sigue las cosechas de la cereza, pera y manzana en California, Oregón y Washington. En noviembre, regresa a México para estar con su esposa e hijos. Él espera ganar entre $15,000 a $25,000 durante su estancia en Estados Unidos. Dice que en lo regular gana un promedio de $100 al día. Algunas cosechas pagan más que otras. Él espera trabajar 200 días o más en ocho meses. En el 2006, él trabajó 210 días. Él no está aquí por razones de turismo o vacaciones, sino para ganar dinero para poder mantener a su familia y construir una casa en Michoacán. Para mucha gente, Luis es la imagen del campesino migrante.

Aunque la cosecha de cereza en The Dalles tiene una apariencia tradicional, hay pocos trabajadores como Luis entre los migrantes con quienes yo trabajé. La mayoría son semejantes a Alberto que vive en un pueblo cerca de Fresno, California. Alberto desempeña el mismo trabajo que Luis, pero con la excepción de pizcar cerezas en The Dalles, su trabajo se encuentra a sesenta millas de donde vive. Se pasa varias semanas cosechando una variedad de frutas durante sus temporadas y se pasa el invierno podando árboles y viñas. Su vida parece estable pues sus hijos asisten a la escuela en el pueblo y él regresa a su casa cada noche.

Aún así, Alberto es un trabajador migrante cuya estabilidad o inestabilidad en la vida está directamente afectada por la movilidad de su trabajo. Muchos trabajadores en la situación de Alberto se sienten tan inciertos como Luis de dónde estarán el próximo mes. La movilidad es la naturaleza de la vida migrante. El trabajo es temporal y el trabajador tiene múltiples especialidades. La inestabilidad del trabajador se complica cuando él o un miembro de su familia no tiene documentos legales. Las redadas de la migra, los rumores y el temor mantienen a las familias en un constante estado de inseguridad. Esta inseguridad les impide establecer una relación con iglesias locales, escuelas y organizaciones comunitarias.

- La fe de los migrantes

Los trabajadores agrícolas migrantes son usualmente católicos. Suelen venir de las zonas rurales de México y América Latina. Su fe está profundamente enraizada en expresiones familiares de la fe. Las oraciones, las celebraciones de fiestas y la devoción a la Virgen nutren la fe. Pocos han recibido instrucción de catequesis significativa. Aún así, el trabajador migrante es profundamente católico y vive esa fe en una sencillez que puede inspirar a aquellos con más altos niveles de educación.

En el 2007, visité a un señor en Michoacán. Él trabajó casi cuarenta años pizcando fruta en California, Oregón y Washington. Cada año, él regresaba a su amado pueblo de Galeana. A la edad de sesenta y dos años, dejó de venir al norte para las cosechas. Cuando entré a su casa, besó mi mano y me dijo: “Padre, es una bendición que usted entre a mi casa”. Buscó a tientas bajo su camisa y sacó una cruz que yo regalo a los trabajadores al final de nuestras misas en los campos migrantes. Es una cruz de plástico sencilla que le recuerda a la gente de la bendición que los trabajadores reciben en la cosecha de la cereza. Me dijo: “Tengo otras dos en mi cuarto. Fue una gran bendición tener misa en nuestra huerta”.

Las misas que yo di en las huertas de The Dalles, Oregón, son una pequeña acción de gracia que recibieron los trabajadores, pero su gratitud a través de los años me ha conmovido. Después de trece veranos de dar misas en los campos durante la cosecha de cereza y once años de dirigir un programa de catequesis para los niños migrantes para prepararlos para su Primera Comunión y Confirmación, la profundidad de la fe católica que se ve en esta gente que está al margen de nuestra iglesia me asombra.

Hay un aspecto desalentador en la fe de los migrantes porque se sienten indignos. Existe un sentimiento profundo de que no son buenos católicos. Continuamente han recibido regaños sobre su indignidad por su falta de asistencia regular a la iglesia, su falta de catequesis y las irregularidades de los matrimonios. Muchos creen que son “malas personas”. Es difícil guiarlos a confiar en la misericordia y el amor de Dios. Por ejemplo, doce hombres que viven en una granja de césped no tienen transporte y viven a varias millas del pueblo más cercano. Trabajan para un contratista diez horas al día, siete días a la semana. Ganan el sueldo mínimo, sin horas extras. Viven en viviendas que provee el agricultor, y pagan $12.50 al día por la comida que les proveen en el campo. Sin transporte y un horario que no les permite tiempo libre, obviamente no pueden asistir a misa regularmente. Sin embargo, si les piden que sean padrinos para un bautismo, las iglesias locales los tratan mal y les niegan que sean padrinos. La gente en los ministerios necesita caminar con los migrantes y entender la vida que viven.

- Las condiciones de trabajo y los sueldos

Las condiciones de viviendas, el trato y el pago del trabajo migrante varían de un lugar a otro. Por la desigualdad en condiciones de trabajo, es difícil hacer generalizaciones. Las condiciones de las viviendas que yo experimenté en Stockton, California eran dramáticamente diferentes de lo que experimenté en The Dalles, Oregón. En The Dalles, los dueños están presentes en las huertas y participan en el trabajo de la cosecha. Conviven con los trabajadores y conocen a la mayoría, si no a todos, de sus empleados. En Stockton, no vi una relación similar entre los dueños y los trabajadores pues la mayoría de los dueños de las huertas emplean contratistas. Es el contratista el que tiene contacto con los trabajadores.

El sueldo no es la única consideración del trabajador migrante al buscar trabajo en una huerta particular o en una granja. El trabajador considera lo que cuesta vivir en esa área durante la cosecha para determinar si vale la pena seguir una cosecha u otra. En algunas comunidades, el dueño de la huerta o el granjero proveen vivienda. En otras áreas, la gente necesita rentar una vivienda o dormir en tiendas de campaña en la parte de atrás de la huerta. Un trabajador comentó sobre su trabajo pizcando cerezas en Stockton y en The Dalles: “Yo gano mejor sueldo en Stockton, pero me queda más ganancia en The Dalles porque el dueño de la huerta provee vivienda”.

El problema de bajos sueldos es la realidad de la economía agrícola. Las ganancias del trabajador migrante son muy modestas, pero cuando los trabajadores pueden reducir sus gastos de vivienda y con trabajo constante, el sueldo les puede alcanzar para vivir dignamente. Los trabajadores de la cosecha tratan de conseguir un buen número de días enteros de trabajo. Cuando el migrante llega a una comunidad, busca trabajo estable para que su sacrificio de estar lejos de su hogar valga la pena. No busca días de descanso.

Los trabajadores reciben el sueldo mínimo que manda la ley estatal para trabajadores agrícolas. En muchas cosechas, existen incentivos para aumentar la producción. En algunas cosechas con incentivos, los trabajadores pueden ganar entre $10 a $20 por hora. Desafortunadamente, no todo el trabajo agrícola tiene niveles de incentivos que aumenten el pago lo suficiente. En la cosecha de la cereza en The Dalles, llegar al nivel de incentivos en una situación normal se logra fácilmente y los trabajadores pueden doblar o hasta triplicar el sueldo mínimo. Visité un vivero en el norte de California que tenía niveles de incentivos que pocos trabajadores podían lograr. Así que básicamente, los trabajadores no podían ganar más que el sueldo mínimo. En algunos trabajos agrícolas, a los trabajadores se les paga por hora. El sueldo mínimo que reciben los trabajadores migrantes no es suficiente para las necesidades de una familia.

A veces hay un mínimo de cuanta fruta o producto puede mandarse al empaque en un día. Si la calidad de fruta que se envía al empaque no es favorable por el daño de la lluvia o algo similar, el empaque puede poner limites en cuanta fruta puede procesarse. Si los trabajadores cumplen con el limite temprano, pueden solamente trabajar de tres a cinco horas al día. Esto disminuye sus ingresos por la temporada. Obviamente, el clima, la calidad y la cantidad de la fruta afectan la cosecha.

Desafortunadamente, hay veces en que el dueño de la huerta o el contratista contratan demasiados empleados y el trabajo en la huerta o el campo se termina en mucho menos de ocho horas. Los campesinos entienden cuando la huerta tiene trabajo limitado por la naturaleza del trabajo agrícola. Sin embargo, los trabajadores sienten resentimiento cuando hay poco trabajo por haber demasiados trabajadores.

Hay serios problemas en los trabajos agrícolas donde sólo se gana por hora. Se les exige a muchos trabajadores que trabajen demasiadas horas, de diez a doce horas por día y de seis a siete días a la semana. No se les paga tiempo extra al trabajar sesenta o setenta horas a la semana. Las largas horas de trabajo son especialmente comunes en las lecherías y los corrales de animales de engorda.

Los contratistas contratan trabajadores para ciertos trabajos o cosechas. Son intermediarios de administración entre el dueño y el trabajador. Los contratistas pueden ser una conveniencia y protección para los dueños en cuanto a los reglamentos gubernamentales de inmigración y protección de trabajadores, pero se quedan con una parte de los ingresos de los trabajadores. Como saben que los empleados quieren más ganancias, los contratistas los manipulan para que trabajen más horas o los intimidan con amenazas de reportarlos a la migra o de quitarles el empleo.

- Evitemos estereotipos

No existe un sólo tipo de trabajador agrícola, contratista ni ranchero. Yo hago estas observaciones de los trabajadores, empleadores y contratistas consciente de que todos están involucrados en el negocio de la agricultura. Las condiciones de los trabajadores varían en muchas situaciones. En algunos casos hay injusticias, pero mi experiencia en general con personas en todos los aspectos de la agricultura es que son buenas personas que trabajan para poner comida en las mesas del mundo. Aquellos que administran a sus trabajadores y a sus campos mal causan pesar al gran número de personas escrupulosas. Las dificultades en las vidas de los trabajadores agrícolas vienen de muchas fuentes.

No hay soluciones fáciles

Lo complejo de las vidas de los migrantes y las realidades de la migración requieren un enfoque integral en los asuntos políticos de inmigración. Lo mismo pasa en los asuntos de la fe. Necesitamos un enfoque integral de evangelización y acercamiento de la Iglesia al campesino. Las respuestas sencillas a problemas complejos causaran división y soluciones insatisfactorias entre la Iglesia y la sociedad.

Los migrantes son fieles, trabajadores y con esperanza. Les di un poco de atención, y me aceptaron como su sacerdote. Su amor es genuino y me hace sentir humilde. Espero que otros también los amen y los cuiden dentro de la sociedad y en nuestra Iglesia.