Migrant Faith, Chapter Five: Who is the Campesino?

(Labor Day Weekend: Last week, I introduced my book, Migrant Faith. My work in Hispanic Ministry brings me into contact with migrant laborers in many industries that rely on manual laborers who are often overlooked in American society. Recently, some attention is given to workers in the production of food, the packing industry, workers in maintenance, construction and transportation. I have worked with people in all industries that use migrant labor. For the next few days, I will present chapters from Migrant Faith. Today and tomorrow, we consider the farm worker, the campesino.)

Who Is the Campesino?

“June 1998: It was 4:15 a.m. in The Dalles, Oregon, when I went with seven migrant workers to begin the harvest. We rode in an old jeep, seven in the jeep, two on the hood. The mayordomo (supervisor of the orchard) was at the wheel. At the top of the hill the workers got out to begin the harvest. The mayordomo said, “Vamos a volar.” (“Let’s fly”). Then we took off to pick up more workers. The Indiana Jones ride at Disneyland is nothing to compare with this. We made three more such trips. Other workers were walking up the hill to begin work. By 5:00 a.m., the hillside was alive with the cherry harvest.

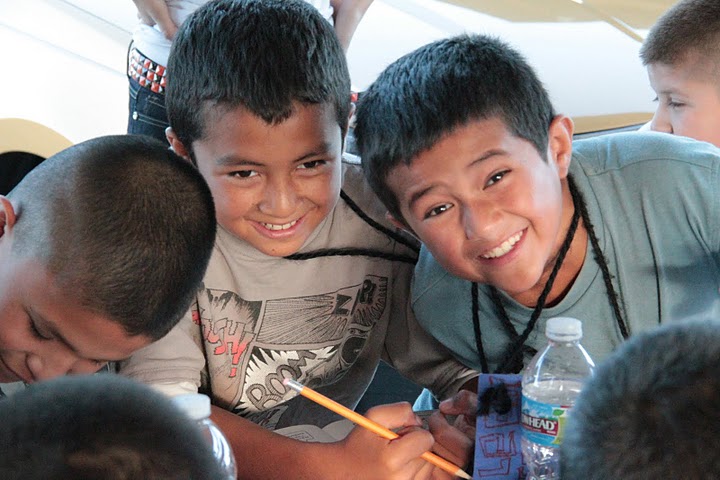

There were many greetings, “Hey, Padre. ¿Dónde está su balde?” (Where’s your bucket?) When light finally filled the hillside, I began to take photos. From the middle of trees laden with cherries, workers cried out, “Padre, take our picture.” Many were whistling or singing softly while they picked cherries. I came to this valley as a missionary to give hope to migrant workers, yet as each day passed, I gained respect and love for these workers.

(from personal journal)

It was 1998 when I had my introduction to migrant farm workers during the harvest in The Dalles, Oregon. Nine years later, in 2007, picking fruit and living with migrant workers was part of my sabbatical study. My first day picking cherries in Stockton there were people in the orchard who asked, “¿Quién es el gabacho trabajando con nosotros?” (“Who is the American working with us?”) Many could not believe it when they were told, “He is a priest.”

I have preached parish missions in rural communities in fifteen states since 1996. Often the missions were presented for one week in English and one week in Spanish. I spent five years working in the Redemptorist Hispanic Initiative in the diocese of Dodge City, Kansas. For two years, I preached parish missions almost exclusively in Spanish in California and Oregon. On May 1, 2009, I became the Director for Multicultural and Campesino Ministry for the diocese of Fresno.

Campesino Ministry offers unique challenges to the ministry of the Church, but it also offers great blessings. My background is as a religious educator, a mission preacher and youth minister. My greatest joy came in organizing a sacramental mission for migrant workers in The Dalles, Oregon. Each year that mission prepared children for First Eucharist, youth and young adults for Confirmation and Eucharist. Couples prepared for the convalidation of their marriages and the baptism of infants.

Campesino – one who works the field

Fifty and sixty years ago the face of the “campesino” was identified with the “migrant” who followed the crops from the South to the North and back to the South. It was easy to identify the migrants. They worked the fields. They lived in groups at camp housing or in tent cities on farms. They were in a community for a specific period of time. When the harvest ended, they moved on. Communities adjusted to the flow of workers during certain times of the year. There were priests and religious who followed some of the workers, but by and large the migrants were invisible to many of our church communities.

Changes in agriculture have reduced the number of people who continue to live in the mobile manner of migrants in the past. While some continue to live working “la corrida,” (the circuit), most live in homes on farms or in small towns and even large cities. In the fruit and vegetable industry, they tend to work within fifty miles of their homes. Their work is often temporary, involving a variety of crops and a variety of skills. Many are uncertain about how long they will remain in a place. They live in the moment. Things outside their control in the forces of climate, economics and political realities form the fluidity of their lives.

Agriculture is an essential human service as people dedicate themselves to the production of food and necessities of life. Modern society often takes agriculture for granted and looks down on it as unworthy of its energy.

Farm work is a noble work as Gerardo E. told me. Gerardo came to the U.S. in the 1970’s, and spent five years working the fields in California, Oregon and Washington. In the 1980’s, he moved to Los Angeles and worked first as a mechanic and later became the manager of a tire store. He worked behind the desk and was making more money than he could ever make in the fields; however, he experienced some uncomfortable changes in his personality. He would lose his temper and he was irritable particularly with his family. He finally told his wife that he was unhappy in his work and that he missed working the fields. They moved to the Sacramento area and he returned to harvest work. With pride Gerardo said, “Padre, today we sent forty tons of cherries to the packing house. Soon these cherries will be on tables in San Francisco, Chicago, New York and London. And tomorrow we will pick another forty tons.” Gerardo said that at the end of the day he leaves the orchard with a belief that he has done something good for the world.

(Tomorrow, the conclusion of this chapter considers some of the special circumstances of campesino life that affect campesino ministry)

(El Día del Labor: La semana pasada, presenté mi libro, La Fe del Migrante. Mi trabajo en el Ministerio Hispano me pone en contacto con trabajadores migrantes en muchas industrias que dependen de trabajadores manuales que a menudo faltan atención en la sociedad estadounidense. Recientemente, se le presta cierta atención a los trabajadores de la producción de alimentos, la industria del empaque, mantenimiento, construcción y transporte. He trabajado con personas de todas las industrias que utilizan mano de obra migrante. Durante los próximos días, presentaré unos capítulos de La Fe del Migrante. Hoy y mañana , consideramos al trabajador agrícola, al campesino.)

¿Quién es el Campesino?

“Junio 1998: Eran las 4:15 de la mañana en The Dalles, Oregón cuando fui con siete trabajadores migrantes a empezar la cosecha. Íbamos en un jeep viejo, siete en el jeep y dos en el cofre. El mayordomo iba al volante. En la cima de la colina, los trabajadores se bajaron para empezar la cosecha. El mayordomo gritó: “¡Vamos a volar!” Luego despegamos para pasar por más trabajadores. La atracción de Indiana Jones en Disneylandia no es nada comparada a esto. Hicimos otros tres viajes. Otros trabajadores iban subiendo la colina a pie para empezar a trabajar. Para las cinco de la mañana, la ladera cobró vida con la cosecha de la cereza.

Todos me saludaban: “¡Eh, Padre! ¿Dónde está su balde?” Al asomarse el sol, empecé a tomar fotos. De en medio de los árboles llenos de cerezas, los trabajadores gritaban: “¡Padre, tome nuestra foto!” Muchos chiflaban o cantaban suavemente mientras pizcaban cerezas. Yo fui a este valle como misionero para darles esperanza a los trabajadores migrantes, pero al paso de los días, los trabajadores se ganaron mi respeto y mi cariño”.

(parte de mi diario personal

En 1998 por primera vez conviví con los trabajadores migrantes durante la cosecha en The Dalles, Oregón. Nueve años después, en 2007, parte de mi estudio sabático era pizcar fruta y vivir con trabajadores migrantes. En mi primer día pizcando cerezas en Stockton, California, unos trabajadores en la huerta preguntaban: “¿Quién es el gabacho trabajando con nosotros?” Cuando les decían: “Es un sacerdote”, muchos no lo podían creer.

He predicado misiones parroquiales en comunidades rurales en quince estados desde 1996. A menudo, las misiones se daban una semana en inglés y una semana en español. Pasé cinco años trabajando el la Iniciativa Hispana Redentorista en la diócesis de Dodge City, Kansas. Por dos años, prediqué misiones parroquiales casi exclusivamente en español en California y Oregón. El primero de mayo del 2009, me convertí en el director del Ministerio Campesino y Multicultural de la diócesis de Fresno, California.

El Ministerio Campesino presenta desafíos únicos al ministerio de la Iglesia, pero también brinda grandes bendiciones. Cuento con experiencia como educador religioso, predicador de misiones, y ministro de jóvenes. Mi mayor alegría fue organizar la misión sacramental para los trabajadores migrantes en The Dalles, Oregón. Cada año esa misión prepara a los niños para su Primera Comunión y a los jóvenes para la Confirmación y la Primera Comunión. La misión también prepara a las parejas para la convalidación de sus matrimonios y el Bautismo de los niños.

El Campesino – uno que trabaja el campo

Hace cincuenta y sesenta años, el rostro del campesino se identificaba con el migrante que seguía la cosecha del sur al norte y de regreso al sur. Era fácil reconocer a los migrantes. Trabajaban en los campos. Vivian en grupos en viviendas en los campos o en campamentos en las granjas. Permanecían en una comunidad por un periodo de tiempo específico. Cuando terminaba la cosecha, ellos seguían su camino. Las comunidades se acostumbraban al movimiento de los trabajadores durante ciertos tiempos del año. Había sacerdotes y religiosas que seguían a algunos de los trabajadores, pero en general los migrantes eran invisibles para muchas de las comunidades religiosas.

Los cambios en la agricultura han reducido el número de gente que continúa viviendo en movilidad como los migrantes en el pasado. Aunque algunos continúan siguiendo la corrida, la mayoría vive en casas en granjas o en pueblos pequeños y hasta en grandes ciudades. En la industria de frutas y verduras, los trabajadores suelen trabajar a cincuenta millas de su hogar. A menudo, su trabajo es temporal, en una variedad de cultivos que requieren una variedad de destrezas. Muchos no saben cuanto tiempo permanecerán en un lugar. Viven el momento. Los elementos fuera de su control como el clima, la economía y las realidades políticas forjan la fluidez de sus vidas.

La agricultura es un servicio esencial en el cual la gente se dedica a la producción de alimentos y las necesidades de la vida. A menudo, la sociedad moderna no valora la agricultura y la menosprecia.

Como Gerardo E. me dijo, el trabajo del campo es un trabajo noble. Gerardo vino a los Estados Unidos en la década de 1970 y pasó cinco años trabajando en los campos en California, Oregón y Washington. En los años de 1980, se mudó a Los Ángeles y primero trabajó como mecánico y después se convirtió en gerente de una tienda de llantas. En la tienda ganaba más dinero de lo que jamás podía ganar en los campos; sin embargo, él experimentó unos cambios incómodos en su personalidad. Perdía el temperamento y se irritaba, particularmente con su familia. Finalmente le dijo a su esposa que no era feliz en su trabajo y que extrañaba el trabajo del campo. Se mudaron al área de Sacramento y él regresó a la cosecha. Con orgullo, Gerardo me dijo: “Padre, hoy enviamos cuarenta toneladas de cerezas al empaque. Pronto las cerezas estarán en las mesas en San Francisco, Chicago, Nueva York y Londres. Y mañana pizcaremos otras cuarenta toneladas”. Gerardo me dijo que al final del día sale de la huerta con la certeza de que ha hecho algo bueno para el mundo.

(Mañana hay continuación)