Migrant Faith, Chapter One (continued)

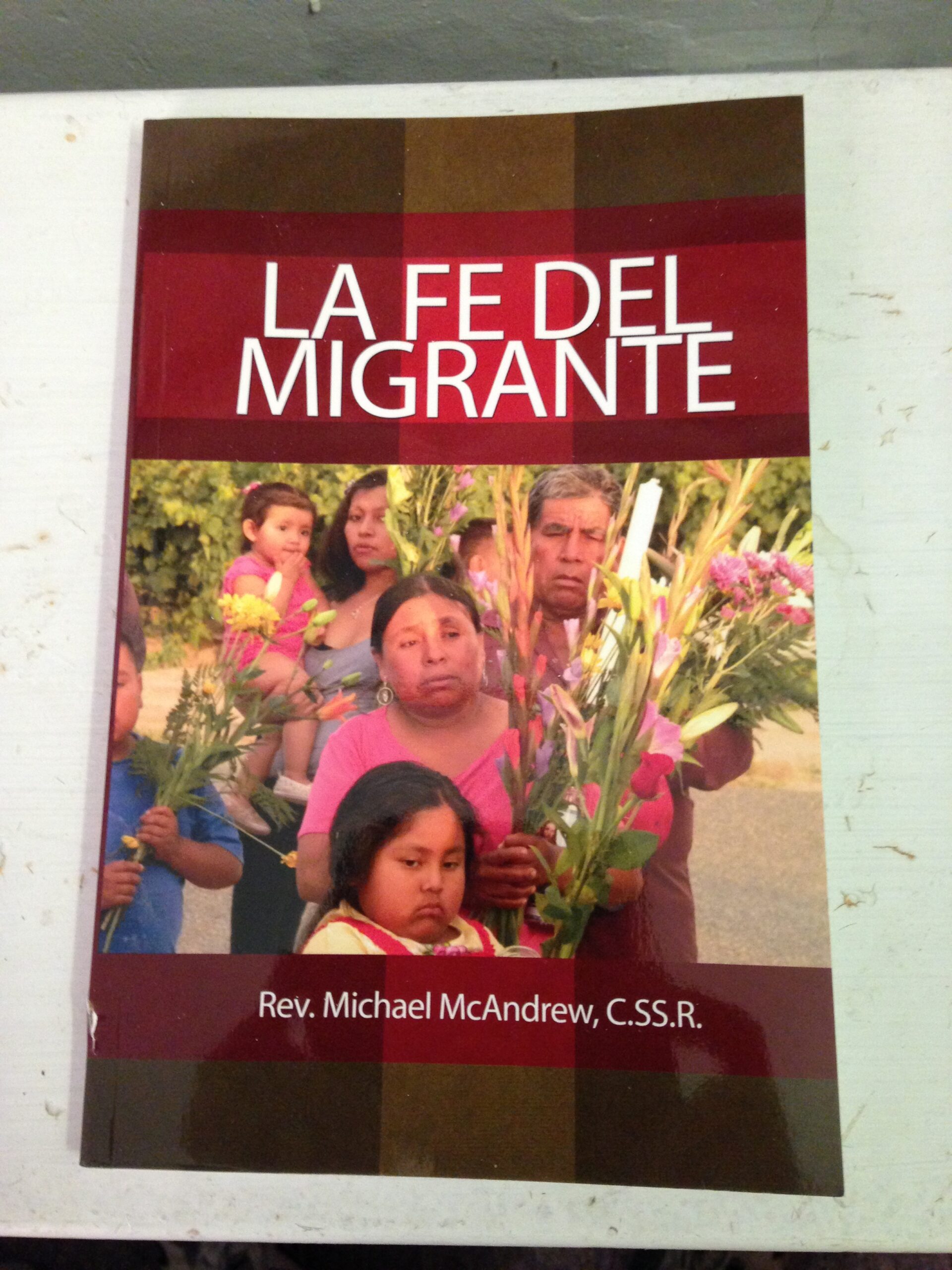

(After writing the Book, Migrant Faith, it is Chapter One that draws comments from migrants that I appreciate most. This summer, I celebrated Mass early in the harvest at an orchard, and before I left workers at that orchard invited me the evening before many were leaving. As several had read my book during the harvest, a woman said, “I have only read chapter one so far, but, Padre, you know us. You know our faith and our struggles.”)

(Después de escribir La Fe del Migrante, es el Capítulo Uno que extrae los comentarios de los migrantes que más aprecio. Este verano, temprano en la cosecha celebré la misa en una huerta, y unos en esa huerta me invitaron a comer antes que ellos salieron. Como varios habían leído mi libro durante la cosecha, una mujer dijo: “Hasta ahora sólo he leído el capítulo uno, pero, Padre, usted nos conoce. Conoce nuestra fe y nuestra lucha”.)

“Accompanying migrants” rather than “working for” the migrants

One of the greatest blessings of my 2007 sabbatical was to enter the world of migrant workers. For four months I traveled with workers, at times living in migrant camps and picking cherries. Some of the time I would stay in rectories learning of the outreach of parishes and dioceses in Oregon, California and Washington. I was able to simply be with the workers rather than do something for them. Often when doing something for someone, we do not recognize that our service places expectations on those we serve. We do not think about how those expectations can burden the poor whom we wish to help.

There are many hardships that migrants encounter. There are forces that crush the spirit of people on the move. There is the experience of separation from loved ones. There are feelings of guilt when the migrant is unable to be present with a parent or relative when they are ill or dying. Many migrants are separated from their spouses and children for long periods of time, even with doubts that they will ever see each other again. There are temptations to forget why they work in a foreign land. The presence of alcohol and loneliness lures people away from their values and crushes their dreams. The search for a better life for themselves and their families can change to materialism. First one buys a new pair of boots, a belt buckle, clothes and then a truck, stereo and television. Casinos appear to be everywhere in more and more rural communities. The lure of individual wants and desires erodes the dignity and traditional ties of the migrant.

In the midst of the hardships and suffering, one still finds great hope and joy in the migrant community. The work is hard, and workers endure many hardships to make a better life for their families. Yet, there is always a reason for a fiesta. And if there is no reason for a fiesta, one will be made up. Among themselves, workers speak of the blessings they receive from God. Religious practices are a mix of traditional and charismatic spirituality.

At times one will encounter a cynicism about religion as people express their frustration with religious leaders whom they accuse of hypocrisy. Under the surface of that cynicism is a combination of frustration with the lack of feeling welcomed in Catholic churches in the United States and a sense of unworthiness. Many tire of the combative comparisons made about Catholic and Protestant religious teaching. The cynicism is expressed in ideas, but the emotion comes from the heart.

The faith of the migrant is found in the heart, el corazón. Faith is part of the identity of the migrant. It is deeply intertwined in all of their relationships. It is expressed in culture, music, family and patriotism. The grito (rallying cry) of Mexican independence includes the identity of being Catholic. “Que viva la raza, que viva la patria, que viva la Virgen.”That rallying cry comes from the heart of people who see their social, political and religious identity as the foundation of their human dignity.

Walking with Migrants

When I first began studying Spanish, Fr. Enrique Lopez, C.SS.R., told me, “I hope you are not one of those American priests who thinks that once you learn Spanish, you know everything that you need to know to work with Mexicans. You need to learn the culture, the history, the feasts and walk with the people. If you will not walk with my people, do not bother learning Spanish.” His advice was harsh, but I cherish his words and have sought to walk with the migrants. Three years later he asked me to preach a parish mission in his parish.

At one point, there was a parish in the diocese of Fresno with no priest. The pastor needed help at first because of illness, and later he retired. For ten months a few priests helped the parish on weekends for Masses. I celebrated Masses in that parish about ten times. The Dean of that region met with the people before assigning a new pastor. One Mexican woman said, “Why can’t you send us Fr. Mike?” The Dean asked, “Why do you want Fr. Mike?” She replied, “Fr. Mike is an American. Not only did he learn our language, he also studied our history and loves our religious practices and feasts. When he explains the story of conversion in Mexico, we leave Mass, proud to be Catholic.” She continued, “Unfortunately other preachers chastise us, and we leave sad. Please, send us Fr. Mike.”

Ministering to the migrant

As a seminarian I spent two summers working with priests in migrant farm worker camps. Conditions of workers and the patterns of life for migrant workers have changed over the years. Issues of immigration, health care, education and workers conditions are always a concern of the Church in serving the needs of migrant workers. There are great challenges facing our Church in the ministries of Catholic Charities and Peace and Justice Ministries in addressing needs of migrants. Yet the priority of all ministries is evangelical and sacramental.

Migrant Ministry needs to focus on welcoming the migrant into our Catholic communities and to make the sacramental presence of Christ available to the People of God. A migrant woman said, “Father, we need you to be our priest. We need you to baptize and teach our children. We need you to show us how to follow Jesus.” In my work as coordinator for Campesino Ministry, I am often asked about issues of immigration, housing for the workers, issues of justice and economic needs. Yet I remind myself often of this woman’s words, “Be our priest”. Collecting clothing and food for the poor is part of the charitable outreach of our church. Working for just immigration reform and working to protect workers’ rights are an important part of migrant ministry, but none of the issues of justice can be more important than what this woman asked, “Teach us and bring us the love of Christ.”

We need to honor and recognize the depth of faith within the campesino community. The faith of migrants is tested by life in a foreign country. The rules of many parishes deny access to many farm workers and their children to the grace of the sacraments. Many farm workers come from a Catholicism rooted in popular religion. While they may have had little formal instruction in the faith, they are firmly established in their Catholic faith through devotions outside the sacramental structures of the faith. However, the faith of many farm workers and their children is tested when the rules of many parishes deny them access to the grace of the sacraments.

When existing programs of sacramental preparation are unable to accommodate the faithful who approach a parish with the proper request to receive the sacraments, pastoral agents must look for alternative approaches that make the sacrament available. Alternative programs need to experiment with scheduling, materials and location for such activities. When an alternative program is successful, the established programs may find themselves challenged to improve their own methods.

The campesino asks the Church for a blessing, the reassurance that the person is right with God. The experience of migration erodes the sense of dignity and self-respect of the person. The migrant is humiliated in many ways as they lose their own identity having to live with false identification, lying and losing oneself to the system of immigration. Furthermore, since the work is difficult and often inconsistent, there is little security and stability in the migrant’s life. And too often when going to church, the migrant experiences chastisement.

Too often, parish sacramental programs for migrants and their children are full of rules that they find difficult to fulfill because of work and the uncertainty of their lives. At the celebration of a birthday for an infant, a worker told me, “Church rules here form barriers that prevent migrants from receiving the grace of the sacraments.” He was speaking about many obstacles that migrants face in bringing children for First Eucharist and Confirmation.

Extraordinary ministry – a challenge to the ordinary

The history of the Church is filled with creative zeal from the time of the Apostles to the present day. St. Paul took the message of Jesus to the Gentiles. He struggled with those who wanted the converts to first get circumcised before they could be received into the Church.

Later, the founders of religious orders formed communities of dedicated people to address needs of people who were not being served in the ordinary experience of the church. Saints Francis of Assisi, Teresa of Avila, Ignatius Loyola, Alphonsus Liguori, Rose Philippine Duchesne, Damien of Molokai, Teresa of Calcutta and many others saw people on the margins of society and experience of the Church who needed to be evangelized and touched by the love of God. In the beginning these founders of religious orders and others made people around them uncomfortable as they met spiritual needs of people whom the ordinary ministry of the Church not only failed to serve, but also failed to even see or acknowledge.

In 1983, in an address to CELAM (Consejo Episcopal Latinoamericano), Pope John Paul II called for a New Evangelization: “Evangelization will gain its full energy if it is a commitment, not to re-evangelize but to a New Evangelization, new in its ardor, methods and expression.” He called on the Church to recognize the changing circumstances of the people whom we serve. The message of the gospel is dynamic. Evangelization is not static. When there are circumstances that need a New Evangelization, new methods are necessary. “New methods” in evangelization do not condemn past methods of catechesis, but rather call on people to be open to the changing reality of the People of God.

Evangelization is not indoctrination. While doctrine is an important part of growing in the faith, the desire to know more about the faith flows from the experience of an encounter with the divine, an encounter with God. In Disciples Called to Witness, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) states, “The New Evangelization seeks to invite modern man and culture into a relationship with Jesus Christ and his Church” (Disciples Called to Witness, p. 6). It is witness that fosters this relationship as Pope Paul VI said, “Modern man listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and if he does listen to teachers, it is because they are witnesses” (Evangelii Nuntiandi, 41).

In literature about the New Evangelization many express concern about the lack of regular attendance at Sunday Mass. A great majority of Catholics in the United States do not participate regularly in Sunday worship. It is more complex than simply attributing this lack of regular attendance to secularization, materialism and individualism. The impact of declining vocations to priesthood, the quality of preaching, and the response to scandalous behaviors of clergy contribute to alienation from the Church. The analysis of participation of Catholics in the Church is not complete if we fail to consider how evangelization is presented.

The Conservative-Liberal polarity of society has badly served us in reflecting on the Pope’s call to New Evangelization. New methods are neither liberal nor conservative. We need to free ourselves to analyze the pastoral realities that we face and seek responses that meet the needs of those asking for God’s blessing. Witness and new methods of evangelization will challenge the status quo of parishes unwilling to enter into frequent evaluation of methods employed in catechesis.

My hope is to invite people in ministry to appreciate the faith and dignity of migrant peoples. I invite the reader to see the migrant not so much as people who need to be evangelized but to be welcomed and to allow them to evangelize us with their faith and hope that has survived such hardships and duress. When we allow ourselves to enter the lives of migrants, we meet them in their needs and allow them to show us the face of Christ. As Jesus said, “I was a stranger and you welcomed me” (Mt. 25:35).

“Acompañando a los migrantes” en vez de “trabajar por los migrantes”

Una de las mayores bendiciones de mi año sabático en 2007 fue entrar en el mundo de los trabajadores migrantes. Por cuatro meses viajé con los trabajadores, a veces viviendo en campos migrantes y pizcando cerezas. Parte del tiempo me quedaba en las rectorías aprendiendo cómo las parroquias y las diócesis en Oregón, California, y Washington se acercaban a la gente. Pude sencillamente estar con los trabajadores en vez de hacer algo por ellos. A menudo, al hacer algo por alguien, no nos damos cuenta de que nuestro servicio impone expectativas en aquellos a quienes servimos. No pensamos como esas expectativas pueden convertirse en un peso para los pobres a quienes ayudamos.

Los migrantes enfrentan muchas dificultades. Existen fuerzas que quiebran el espíritu de gente en movimiento, como la separación de seres queridos. Hay sentimientos de culpabilidad cuando un migrante no puede estar presente cuando un padre o pariente está enfermo o agonizando. Muchos migrantes están separados de sus cónyuges e hijos por largos periodos de tiempo, con dudas de volver a verse. Existen tentaciones para olvidar porqué trabajan en una tierra extraña. El alcohol y la soledad alejan a la gente de sus valores y aplastan sus sueños. La búsqueda de una mejor vida para ellos y su familia se puede convertir en materialismo. Primero uno compra un par de botas nuevas, una hebilla, ropa y luego una camioneta, estéreo y televisión. Tal parece que los casinos aparecen por todos lados más y más en comunidades rurales. La tentación de deseos individuales disminuye la dignidad y unidad tradicional del migrante.

En medio de las dificultades y sufrimientos, uno aún encuentra gran esperanza y alegría en la comunidad migrante. El trabajo es arduo y los trabajadores sobrellevan muchas dificultades para lograr una mejor vida para sus familias. Sin embargo, siempre hay una razón para una fiesta y si no hay razón, se inventan una. Entre ellos, los trabajadores hablan de las bendiciones que reciben de Dios. La práctica religiosa es una combinación de espiritualidad tradicional y carismática.

A veces se nota cierto cinismo tocante a la religión cuando la gente expresa su frustración hacia líderes religiosos a quienes acusan de hipocresía. Detrás de ese cinismo hay una combinación de frustración al no sentirse bienvenidos en las iglesias católicas en los Estados Unidos y un sentimiento de devaluación personal. Muchos se cansan de las comparaciones combativas que se hacen de las enseñanzas católicas y protestantes. El cinismo se expresa en ideas, pero el sentimiento viene del corazón.

La fe del migrante se encuentra en el corazón. Parte de la identidad del migrante es su fe. Está profundamente entrelazada en todas sus relaciones. Se expresa en la cultura, la música, la familia y el patriotismo. El “grito de la independencia mexicana” incluye la identidad de ser católico: “¡Qué viva la raza! ¡Qué viva la patria! ¡Qué viva la Virgen!” Ese grito viene del corazón de la gente que ve su identidad social, política y religiosa como la base de su dignidad humana.

El caminar con los migrantes

Cuando empecé a estudiar español, el Padre Enrique López, C.SS.R., me dijo: “Espero que no seas uno de esos que piensa que cuando aprende el español, ya sabe todo lo que necesita saber para trabajar con los latinos. Necesitas conocer las costumbres, la fe y la lucha de mi pueblo. Si no caminas con mi pueblo, no te molestes en aprender español”. Su consejo fue rígido, pero valoro sus palabras y he procurado caminar con los migrantes. Tres años después, me pidió que predicara una misión en su parroquia.

Hace poco, una parroquia en la diócesis de Fresno no tenía sacerdote. Al principio, el pastor necesitaba ayuda porque estaba enfermo y después se jubiló. Por diez meses, algunos sacerdotes ayudaron a celebrar misas los fines de semana. Yo di diez misas en esa parroquia. Antes de asignar a un nuevo pastor, el Deán de esa región se reunió con la gente para prepararla para la llegada del nuevo pastor. Una señora le dijo: “¿Porqué no nos manda al Padre Miguel”? El Deán les preguntó:”¿Porqué quieren al Padre Miguel”? Ella le respondió: “Padre Miguel es un americano. No solo aprendió nuestro idioma, sino que estudió nuestra historia y le encantan nuestras prácticas religiosas y festividades. Cuando él explica de la historia de la conversión en México, salimos de la misa orgullosos de ser católicos”. Ella continuó: “Desafortunadamente, otros predicadores nos regañan y nos vamos tristes. Por favor, mándenos al Padre Miguel”.

Dando ministerio al migrante

Como seminarista, pasé dos veranos trabajando con sacerdotes en los campos de trabajadores migrantes. Las condiciones de trabajo y el estilo de vida de los trabajadores migrantes han cambiado en los últimos años. Los asuntos de inmigración, la salud, la educación y las condiciones de trabajo de los campesinos son siempre la preocupación de la Iglesia al servir las necesidades de los migrantes. Nuestra Iglesia enfrenta grandes retos al responder a las necesidades de los migrantes en los Ministerios de Caridades Católicas y en los Ministerios de Paz y Justicia. Sin embargo, la prioridad de todo ministerio es evangélica y sacramental.

El Ministerio Migrante necesita enfocarse en acoger al migrante en nuestras comunidades católicas y en hacer la presencia sacramental de Cristo accesible para el Pueblo de Dios. Una mujer migrante me dijo: “Padre, no necesitamos que usted sea nuestro trabajador social ni nuestro abogado. Necesitamos que sea nuestro sacerdote. Necesitamos que bautice y enseñe a nuestros hijos. Necesitamos que nos muestre como seguir a Jesús”. En mi trabajo como coordinador del Ministerio Campesino, a menudo me preguntan sobre asuntos de inmigración, vivienda para trabajadores y asuntos de justicia y necesidades económicas. Sin embargo, seguido me acuerdo de las palabras de esta mujer: “Sea nuestro sacerdote”. Parte del servicio caritativo de nuestra Iglesia es juntar ropa y comida para los pobres. Luchar por una reforma migratoria justa y luchar por la protección de los derechos de los trabajadores son otra parte importante del ministerio migrante, pero ninguno de estos asuntos de justicia puede ser más importante que lo que esta mujer me pidió: “Enséñenos y tráiganos el amor de Cristo”.

Necesitamos honrar y reconocer la profunda fe de la comunidad campesina. Muchos campesinos vienen de un catolicismo enraizado en la religión popular. Aunque hayan tenido poca instrucción formal de la fe, están firmes en su fe católica por medio de las devociones fuera de las estructuras sacramentales de la fe. Sin embargo, la fe de muchos campesinos y sus hijos se pone a prueba cuando las reglas de muchas parroquias le niegan acceso a la gracia de los sacramentos.

Cuando los programas existentes de preparación sacramental no pueden dar acceso a los fieles a que se acercan a la parroquia para pedir los sacramentos, los agentes pastorales deben buscar alternativas para proveer los sacramentos. Los programas alternativos necesitan experimentar con horarios, útiles y lugares para esas actividades. Cuando un programa alternativo tiene éxito, los programas establecidos pueden encontrarse con el reto de mejorar sus propios métodos.

El campesino pide la bendición de la Iglesia para reafirmar su relación con Dios. La experiencia migratoria devalúa la dignidad y respeto de la persona. Al migrante se le humilla de muchas maneras: al perder su identidad, al tener que vivir con identificación falsa, al mentir y al perderse en el sistema de la inmigración. El trabajo es difícil e inconsistente. Existe poca seguridad y estabilidad en la vida del migrante. Y a menudo, al acercarse a la Iglesia, recibe castigos.

Con frecuencia, los programas sacramentales de las parroquias están llenos de reglas que son muy difíciles de satisfacer por razones de trabajo y por la incertidumbre de las vidas de los migrantes y sus familias. En la celebración de un cumpleaños de un niño, un trabajador me dijo: “Aquí las reglas de la Iglesia crean barreras que impiden que los migrantes reciban la gracia de los sacramentos”. Él hablaba de los muchos obstáculos que los migrantes enfrentan al traer a sus hijos a recibir la Primera Comunión y la Confirmación.

Ministerio extraordinario – Un reto al ministerio ordinario

La historia de la Iglesia está llena de fervor creativo desde el tiempo de los apóstoles hasta el presente. San Pablo llevó el mensaje de Jesús a los no judíos. Él lucho contra aquellos que querían que los convertidos se circuncidaran antes de ser aceptados en la Iglesia.

Después, los fundadores de ordenes religiosas formaron comunidades de personas dedicadas a atender las necesidades de aquellas personas que no recibían atención en la experiencia ordinaria de la Iglesia. Los Santos, por ejemplo, Francisco de Asís, Teresa de Ávila, Ignacio Loyola, Alfonso Liguori, Rose Philippine Duchesne, Damien de Molokai, Teresa de Calcuta y muchos otros vieron a la gente al margen de la sociedad y de la experiencia de la Iglesia que necesitaba evangelización y sentir el amor de Dios. Al principio, estos fundadores de órdenes religiosas y otros incomodaron a otras personas a su alrededor al atender las necesidades espirituales de la gente a quien el ministerio ordinario de la Iglesia no solo había fracasado en servir, sino que había fracasado en verla o reconocerla.

En 1983, en un discurso a CELAM (El Consejo Episcopal Latinoamericano), el Papa Juan Pablo II pidió una nueva evangelización: “La evangelización tomará su mayor energía si es un compromiso, no para re-evangelizar, sino para una nueva evangelización, nueva en su ardor, métodos, y expresión”. Pidió a la Iglesia reconocer la realidad cambiante de la gente a la que servimos. El mensaje del evangelio es dinámico. La evangelización no es estática. Cuando hay casos que necesitan una nueva evangelización, se necesitan nuevos métodos. Los “nuevos métodos” en evangelización no condenan los métodos antiguos de catequesis, sino que piden a la gente que esté libre de prejuicios a la cambiante realidad del pueblo de Dios.

La evangelización no es adoctrinamiento. Mientras que la doctrina es una parte importante del crecimiento en la fe, el deseo de conocer más sobre la fe viene de la experiencia de un encuentro con lo divino, un encuentro con Dios. En Disciples Called to Witness, (Discipulos Llamados a Atestiguar), el USCCB (Conferencia Episcopal Católica de los Estados Unidos) dice: “La nueva evangelización busca invitar al hombre moderno y a la cultura a entrar en una relación con Jesucristo y su Iglesia” (Disciples Called to Witness, p.6). El Papa Pablo VI dijo que el testimonio alimenta esta relación: “El hombre moderno está más dispuesto a escuchar a los testigos que a los maestros, y si escucha a los maestros, es porque son testigos” (Evangelii nuntiandi, 41).

En la literatura sobre la nueva evangelización, muchos muestran preocupación por la falta de asistencia en la misa dominical. Una gran mayoría de los católicos no participa regularmente en los servicios dominicales. Esto es más complejo que simplemente atribuir la falta de asistencia regular a la secularización, el materialismo y el individualismo. El impacto de la disminución en las vocaciones al sacerdocio, la calidad del predicar y la respuesta a los comportamientos escandalosos del clérigo contribuyen al distanciamiento de la Iglesia. El análisis de la participación en la Iglesia no está completo si no tomamos en cuenta cómo se presenta la evangelización.

La polaridad entre conservadores y liberales no nos ha permitido reflexionar sobre el llamado del Papa a la evangelización. Los nuevos métodos no son ni liberales ni conservadores. Necesitamos permitirnos analizar las realidades pastorales que enfrentamos y buscar soluciones que responden a las necesidades de los que piden la bendición de Dios. El testimonio y los nuevos métodos de evangelización retarán el estatus quo de las parroquias que no estén dispuestas a evaluar con frecuencia los métodos utilizados en la catequesis.

Mi deseo es invitar a las personas envueltas en ministerios a apreciar la fe y dignidad de la gente migrante. Invito al lector a ver a los migrantes no tanto como personas que necesitan ser evangelizadas, sino a acogerlos y permitirles que nos evangelicen con su fe y con su esperanza que ha sobrevivido tantas dificultades. Al darnos la oportunidad de entrar en las vidas de los migrantes, conocemos sus necesidades y les permitimos mostrarnos a Cristo. Como dijo Jesús: “Fui forastero y ustedes me recibieron en su casa” (Mt. 25,35).