17. “Walk with my people” : Casa San Alfonso y la Migra (Cont.)

Cuando la Migra llama a la puerta (cont.)

Miguel e Inés tenían dos niños, de siete y cuatro años. Dado que los dos niños eran ciudadanos estadounidenses, asumí que la dificultad extrema no debería ser difícil de probar. Me sorprendió que los niños ciudadanos tuvieran tan poca protección de ser separados de sus padres o forzados a dejar los Estados Unidos para vivir en un país que no conocían. Su oportunidad de educación sería dramáticamente limitada en el país de sus padres. Sin prueba de enfermedad o discapacidad grave que no pudiera tratarse en el país de los padres, simplemente no cumplían con los requisitos ordinarios de la ley. La bendición de la buena salud, las buenas calificaciones y la buena disposición de los niños no ayudaron en la corte de inmigración.

Había mucha dificultad para demostrar su presencia en Estados Unidos. Tenían que demostrar su presencia durante siete años consecutivos y solo llevaban siete años y dos meses en el país. Su hijo mayor nació cinco meses después de su llegada y los primeros registros médicos no cumplieron con el requisito de siete años. Vivieron con parientes durante los primeros seis meses y su único ingreso provenía del trabajo de jornalero que pudieron encontrar. Solo teníamos testimonios de amigos y familiares sobre su presencia. Luego, una noche durante la cena, les pedí que contaran la historia de sus primeras semanas aquí otra vez. Cuando hablaron sobre el bautismo de una sobrina el primer domingo en los Estados Unidos, les pregunté ¿cómo podían demostrar que estaban presentes? Dijeron que eran los padrinos. El certificado de bautismo nos dio algo de esperanza, pero no sabíamos si sería aceptado por la corte.

La audiencia judicial fue el 6 de enero, fiesta de la Epifanía. Después de una breve oración, entramos al tribunal preparados para presentar nuestros mejores argumentos a favor de la suspensión de la deportación de Miguel, Inés y sus dos hijos. Nuestro caso empezó bien. El abogado del INS comenzó por no impugnar la presencia de siete años de Miguel e Inés. Tampoco cuestionó su buen carácter. El juicio solo se basó en probar las dificultades extremas causadas a los ciudadanos estadounidenses por la deportación de Miguel e Inés.

Sabíamos que nuestro caso no dependía de lo que normalmente cumplía con la definición de dificultad extrema de la corte. Presentamos solo dos testigos, el empleador de Miguel y yo. Hablé de la importancia de crecer en medio de una familia. La deportación daría lugar a que los niños fueran separados de sus padres o tuvieran que crecer en un país totalmente ajeno a ellos. Los dos niños no tenían parientes que vivieran fuera de Estados Unidos. Alejarlos del amor y apoyo de tías, tíos y primos privaría a estos niños ciudadanos de la oportunidad de prosperar y privaría a la comunidad estadounidense de niños ciudadanos saludables y productivos en el futuro. Durante todo mi testimonio, pensaba que el juez me detuviera y no me escuchara. No siguió con ninguna pregunta. No tenía idea de si mi testimonio ayudó o perjudicó nuestro caso.

Tras mi testimonio, el empleador de Miguel dijo que era dueño de varios restaurantes y describió a Miguel como su mejor chef. Dijo que en veinte años en el negocio de restaurantes, había empleado a más de 2.000 empleados y Miguel era su mejor empleado. Dijo: “Puede que no considere mi necesidad comercial como una dificultad extrema, pero su ausencia causará dificultades extremas para mí y los empleados que supervisa”.

Cuando el juez dio su decisión, comenzó a expresar la naturaleza inusual de nuestros argumentos. Dijo que era inusual que un sacerdote diera una súplica tan apasionada por los niños ciudadanos. Señaló que un empresario dispuesto a testificar con tanta fuerza por un empleado indocumentado era la primera vez en su corte. Otorgó la cancelación de la deportación y les dijo a Miguel e Inés que con esta decisión recibirían la residencia permanente. Dijo que en cinco años serían elegibles para convertirse en ciudadanos estadounidenses y esperaba que aprovecharan la oportunidad de convertirse en ciudadanos.

Años después:

Me reuní con la familia 27 años después de que ganamos el caso de inmigración. En los años transcurridos desde que Miguel e Inés recibieron la residencia permanente en los Estados Unidos, se convirtieron en ciudadanos estadounidenses. Fueron bendecidos con una niña diez años después. Los dos chicos están casados y tenían muy poca memoria de la época del caso. Sus esposas querían escuchar la historia del caso migratorio de Miguel e Inés. Inés sacó una caja de archivo con toda la documentación que guardó de la preparación del juicio. Mostró una carta del abogado escrita aproximadamente a las cuatro semanas antes del caso en la que les advertía que no podíamos ganar el caso. Quería prepararlos para la probabilidad de que tuvieran que abandonar el país. No estoy seguro de qué tan bien entendieron la carta. Le pregunté a Inés cuánta presión sintió durante los cuatro meses de preparación para el juicio. Ella dijo: “Nunca sentí ninguna presión. Nos dijiste que íbamos a ganar”. Me alegro de que tuviera la confianza que nos faltaba a Philip y a mí. Este caso, abrió la puerta a unas relaciones muy interesantes con “la Migra”.

Poco después de la decisión en el caso de Miguel e Inés, fui a agradecer al Sr. Joe Greene, el Director del INS, por su ayuda en el caso.

(Mañana: Mi Amigo, Joe Greene)

When la Migra knocks on the door (cont.)

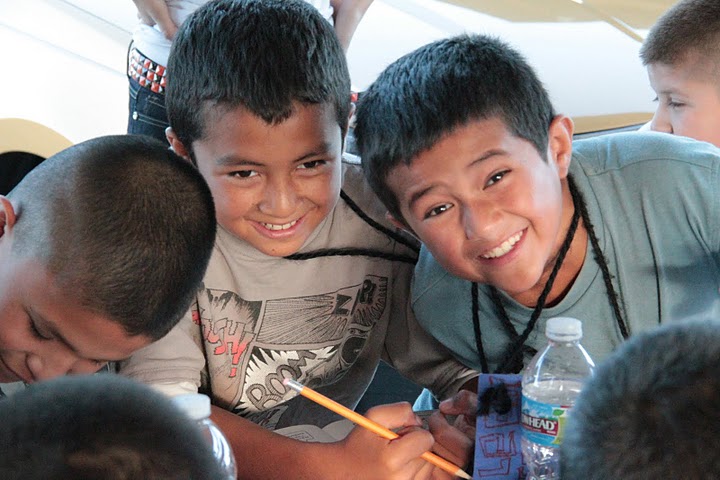

Miguel and Ines had two boys, ages seven and four. Since the two children were U.S. citizens, I assumed that extreme hardship should not be difficult to prove. I was surprised that citizen children had so little protection of being either separated from their parents or forced to leave the U.S. to live in a country that they did not know. Their opportunity for education would be dramatically limited in the country of their parents. Without proof of serious illness or disability that could not be treated in the country of the parents, they simply did not meet the ordinary requirements of the law. The blessing of good health, good grades and the good disposition of the children were not helpful in immigration court.

We had difficulty proving their presence in the United States. They had to demonstrate their presence for seven consecutive years, and they had only been in the country for seven years and two months. Their oldest son was born five months after their arrival and the first medical records missed the seven-year requirement. They lived with relatives for the first six months and their only income was from day labor work that they could find. We only had testimonies from friends and relatives about their presence. Then one evening at dinner, I asked them to tell the story of their first few weeks here when they talked about the baptism of a niece on their first Sunday in the United States. When I asked how they could prove that they were present, they said that they were the godparents. The baptismal certificate gave us some hope, but we did not know if it would be accepted by the court.

The court hearing was on Jan. 6, the feast of the Epiphany. After a brief prayer, we entered the court prepared to present our best arguments for suspension of deportation for Miguel, Ines and their two boys. Our case began well. The INS lawyer began by not contesting the seven-year presence of Miguel and Ines. He also did not contest their good character. The trial then hinged on proving extreme hardship caused to U.S. citizen/s by the deportation of Miguel and Ines.

We knew that our case did not depend on what ordinarily met the court’s definition of extreme hardship. We presented only two witnesses, Miguel’s employer and me. I spoke of the importance of growing up in the midst of a family. Deportation would either result in the children being separated from their parents or having to grow up in a country totally foreign to them. The two children had no relatives living outside of the United States. Taking them away from the love and support of aunts, uncles and cousins would deprive these citizen children of the opportunity to thrive and deprive the American community of healthy, productive citizen children in the future. All through my testimony, I expected the judge to stop me and fail to hear me out. He did not follow up with any questions, so I had no idea if my testimony helped or hurt our case.

Following my testimony, Miguel’s employer said that he owned several restaurants and described Miguel as his best chef. He said that in twenty years in the restaurant business, he had employed over 2,000 employees and Miguel was his best employee. He said, “You may not consider my business need as extreme hardship, but his absence will cause extreme hardship for me and the employees that he supervises.”

When the judge gave his decision, he began expressing the unusual nature of our arguments for hardship. He said it was unusual to have a priest give such a passionate plea for citizen children. He noted that a businessman willing to testify so strongly for an undocumented employee was a first in his court. He granted a cancelation of removal and told Miguel and Ines that with this decision they would receive permanent residence. He said that in five years they would be eligible to become U.S. citizens, and he hoped that they would take advantage of the opportunity to become citizens.

Years later:

I met with the family 27 years after we won the immigration case. In the years since Miguel and Ines received permanent residence in the United States, they became U.S. citizens. They were blessed with a baby girl ten years later. The two boys are married, and they had very little memory of the time of the case. Their wives wanted to hear the story of Miguel and Ines’ immigration case. Ines brought out a file box with all the documentation that she saved from the preparation of the trial. She showed a letter from the lawyer written about four weeks into the case that advised them that we could not win the case. He wanted to prepare them for the likelihood that they would have to leave the country. I am not certain how well they understood the letter. I asked Ines how much pressure she felt during the four months preparing for the trial. She said, “I never felt any pressure. You told us that we were going to win.” I am glad that she had the confidence that Philip and I lacked. This case, opened the door to some very interesting relationships with “la Migra.”

Shortly after the decision in the case of Miguel and Ines, I went to thank Mr. Joe Greene, the Director of INS for his help on the case.

(Tomorrow: My friend, Joe Greene)

Oh Jesús, tú nos llamas: “Síganme”. Bendice, Señor, a todos los que acogen tu llamado. Puede que el camino no sea fácil, pero tenemos la confianza de que todo es posible si caminamos contigo. Que este viaje nos abra los ojos a las maravillas de tu amor por nosotros. Oramos por toda tu gente, por todos los creyentes e incrédulos, por los líderes y seguidores. Oramos por la sanación, el perdón, la compasión, la justicia y la paz. Oramos para que, al seguirte, nosotros también podamos ser pescadores de hombres. Bendícenos en nuestro viaje.

O Jesus, you call us, “Come after me.” Bless, O Lord, all who welcome your call. The path may not be easy, but we have confidence that all things are possible if we walk with you. May this journey, open our eyes to the wonders of your love for us. We pray for all your people, for all believers and unbelievers, for leaders and followers. We pray for healing, for forgiveness, for compassion, for justice, for peace. We pray that as we follow you, we too can be fishers of men. Bless us on our journey.